Picture for a moment the television series Mad Men and the set’s rows and rows of “girls” at their utilitarian desks doing the company’s work while the executives hang out in lavishly furnished corner offices.

Shift to the present day: the show’s producers and writers—half of whom would have been those typists—in the office pecking at computers the size of stenographers’ tablets. Moveable walls divide the space into cubicles that contain matching L-shaped desks, shelves, and file drawers, all fitted together in an organized reconfigurable arrangement. Like them or not, cubicles and furniture systems are in the DNA of the workplace.

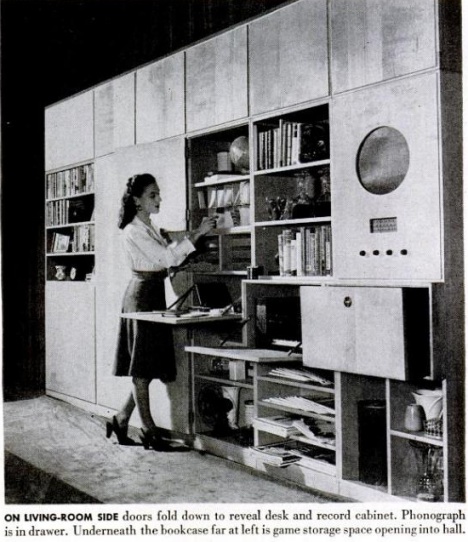

How did we get here? At a rare exhibition focused on industrial designer George Nelson, I learned about one of those forces. In 1945, Life magazine published an article about George Nelson’s Storage Wall, an innovative—and controversial—modular storage system for the home. Soon afterwards, Herman Miller founder D.J. De Pree approached Nelson and asked him to be the company’s director of design. Under George Nelson’s influence, and with teams that included designers like Charles and Ray Eames and Isamu Noguchi, Herman Miller became driven by design, producing iconic mid-century modern sofas, chairs, and office furniture.

One classic is the swag leg office chair, designed in 1958 and still sold by Herman Miller. Nelson wanted to achieve beauty and human-oriented function. He also considered manufacturability. He began with elegantly sculpted legs of chromed steel tubing, insisting that they be machine made, prefinished, and beautiful. To form that curve, the solution turned out to be the swaging process, which would apply pressure to a steel tube to taper and curve it to the exact shape Nelson wanted.

The Swag Leg Chair’s design also simplified other operations. The chair was meant to be knocked down for shipping, and easily assembled by the customer—Nelson made it just a matter of inserting and tightening a screw. At the same time as shipping was optimized, final assembly cost was effectively transferred to the customer.

Six years after the debut of the Swag Leg Chair, Robert Propst and George Nelson began to prototype a distinctive group of freestanding units that eventually became Herman Miller’s Action Office system, a reconfigurable line of office furniture. (Nelson is credited with designing the system’s L-shaped desk that most of us have used all our working lives.) The resulting product line was introduced in 1968 and cubicle culture began.

At Herman Miller, this degree of innovation was made possible by trust. When DePree spoke, the designers listened to him as the man who had to make the decisions. When the designers came up with designs that were different and risky, DePree listened to them.

Trust was at the heart of principles D.J. DePree established for the company’s designers:

• What they make is important,

• Design is integral,

• The product must be honest,

• They decide what they make,

• A market for good design exists.

DePree believed that honesty is the best policy, the customer is entitled to the best quality, workers are entitled to respect and fair compensation, and designs have to be the best regardless of prevailing fashions. To Nelson, this core of meaning is what made innovation possible.

Herman Miller today is a design, manufacturing, and management leader. The company has been recognized for its expertise in lean manufacturing. The workforce is made up of employee-owners who drive continuous improvement and share in the company’s profits. The company sources half of the value of materials and parts for furniture manufactured in west Michigan from within a 50-mile radius, and almost 90% from within North America. Close relationships with both dealers and suppliers allow Herman Miller to gain valuable input and to collaborate on expanding its lean evolution.

What do I take away from this story? The artist/designer’s vision can change markets when leadership listens and balances art and the practicalities of manufacturing. Respect and principles make innovation possible.

Karen Wilhelm has worked in the manufacturing industry for 25 years. She publishes the blogs, Lean Reflections, which has been named as one of the top ten lean blogs on the web.