Why Failure Isn’t Always Bad When It Comes to Lean Leadership

Those of us in the lean community repeatedly see leaders who are ineffective and even set their organizations back. What you may be surprised to learn is that, often, the most destructive leaders are strong, decisive, and take charge of difficult situations.

Those of us in the lean community repeatedly see leaders who are ineffective and even set their organizations back. What you may be surprised to learn is that, often, the most destructive leaders are strong, decisive, and take charge of difficult situations.

Scott Adams, creator of Dilbert, wrote an entertaining and insightful book entitled, How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big, advising people on how to succeed in life. In the book, he, perhaps a bit cynically, observes that decisiveness is often seen as leadership.

“Keep in mind that most normal people are at least a little bit uncertain when facing unfamiliar and complicated situations,” he wrote. “What people crave in that sort of environment is anything that looks like certainty. IF you can deliver an image of decisiveness, no matter how disingenuous, others will see it as leadership.”

Incidentally, this seems to contradict another Scott Adams observation on the same page:

“The world is a complicated place, and often we’re only guessing which path will be best. Anyone who is confident in the face of great complexity is insane.”

The reconciliation is that Adams does not say decisiveness will make you right, only that people desperate for certainty will perceive you as a leader.

Cultural studies find Japanese people are particularly averse to uncertainty. Yet, Toyota recognizes and directly addresses uncertainty. Their countermeasure is not to pretend they are decisive, but rather to admit what they do not know and be open to frequent experimentation. Failure is not only an option, but in a sense, it is desirable. When we sincerely try to accomplish something challenging, we are sometimes going to fail, and the gap between what we expected to happen and what, in fact, did happen is how we learn. For Toyota, gradual learning through experience is its antidote to the challenge of succeeding in a complex world.

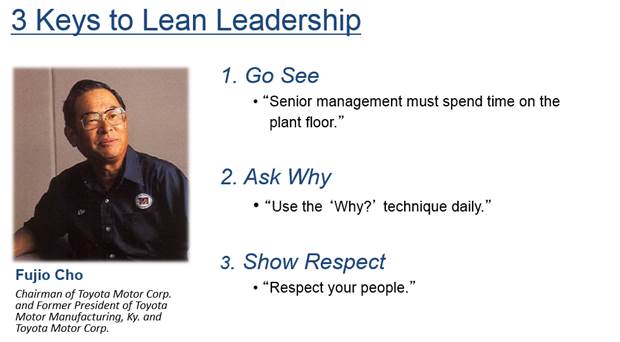

Fujio Cho, first president of Toyota’s Georgetown, Kentucky plant and ultimately president of Toyota globally, was in many ways the archetypal Toyota leader. He was bright, philosophical, humble, kind, and he loved people. In return, people loved and followed him, many for life. I often hear people who served under Cho say decades later, “When I face a difficult situation, I ask myself, ‘What would Mr. Cho do?’”

As displayed below, Mr. Cho had a simple three-part prescription for effective leadership:

In Toyota, “respect for people” has a meaning beyond being fair and reasonable. Respect challenges people to be their best. The primary role of leaders is to develop people, which requires being present where the work is being done, understanding the actual situation, understanding the challenges in the complex environment people face, and then helping people overcome obstacles to achieve levels of performance they do not believe are possible.

Doing this requires biting your tongue, letting others you are developing struggle to find answers, and at times, even letting them fail. The Toyota leader accepts uncertainty. This is why they need to see and challenge their own assumptions about what is happening and why. First impressions about the causes of problems are probably wrong. But, until you dig deeper by asking “why” repeatedly, a leader will not understand the root cause and cannot effectively guide those he is trying to develop.

When I interviewed Akio Toyoda in 2010 about Toyota’s recall crisis, he explained that Toyota was growing faster than it was developing people. For example, when he first joined the company, he was assigned to Toyota’s Operations Management Consulting Division (OMCD) which taught the Toyota Production System to suppliers.

“I was very severely trained at OMCD. And what they taught there was not the answers to the question, it was more question, question, question,” he said. “The process of arriving at the root cause took about two months. But my senior person just above myself, he was able to get the right answer in two weeks. But if you go to a higher level of expertise, like the head of OMCD, he could get the answer within two minutes maybe. The problem however is that the mentor knows the answers already so when people are working under the pressure of time the mentors are irritated and mentors would give the answer to the juniors.”

I was motivated to write about leadership due to my efforts to teach to others what I learned from Toyota. I found that a small percentage was able to seriously improve its organization’s performance and sustain a higher level. In every case, those successful had an exceptional leader who fit the Toyota model. Most others were thinking and acting in a very different way than Fujio Cho suggested, with barriers to each of his three recommendations:

1. Anyplace but where people are working—It is not clear to me what these more traditional leaders do, but they are rarely where people are working to improve value to customers. They seem to travel from meeting to meeting talking to peers and shareholders. Busy, busy, busy doing little that adds value.

2. Faking Certainty—Asking “why” suggests you do not know. The leader who feels pressured to appear decisive has to act like he knows.

3. Egoism—Showing respect for others takes a high level of self-confidence and maturity. The egotistical leader lacks that maturity. In his study of great companies, Jim Collins, author of Good to Great, found that the egotistical leader is an impediment to greatness.

I agree with Scott Adams’ observations that people who fear uncertainty are likely to perceive decisive people as leaders. Obviously, there are crises that require decisiveness, but a leader who wants to develop people will not feed the fear of those less confident by feigning decisiveness. Rather, these people need a leader who encourages them to try to overcome their challenges and grow so they will become effective leaders too.

Dr. Jeffrey Liker is professor of industrial and operations engineering at the University of Michigan and author of The Toyota Way. He leads Liker Lean Advisors, LLC and his latest book (with Gary Convis) is The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership.

Some opinions expressed in this article may be those of a contributing author and not necessarily Gray Construction.

- Category:

- Opinion

- Manufacturing

Some opinions expressed in this article may be those of a contributing author and not necessarily Gray.