To Improve Manufacturing, Improve your Services

There seems to be a good deal of confusion about the differences in the manufacturing and services sectors. Manufacturing companies are often thought of as big factories, when in reality, there is often just as many services offered as there are in organizations.

Manufacturing vs. Services

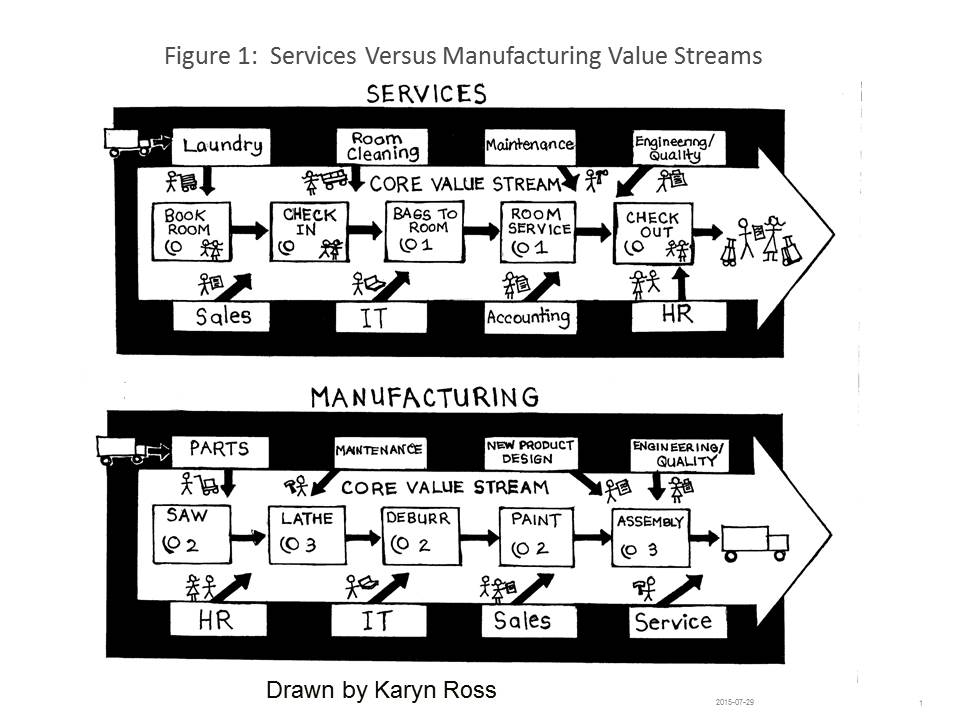

Manufacturing is typically defined as the production of tangible objects that can be stored for later use. If the value-added is intangible and cannot be stored, it is deemed a service. This is reasonable enough, right? On the other hand, a service organization often carries physical goods or requires a physical infrastructure such as a telecommunications company, hospital, hotel, grocery store, and even an online store. Look beyond the customer and you will see a lot of physical items being moved around, a lot of equipment being repaired, and a lot of highly routine processes such as standard answers to customer questions. The figure below shows a manufacturing value stream (For example: assembling manufactured components) compared to a service value stream such as a hotel. Notice that many of the support functions that are critical to the hotel are similar to manufacturing and many of the support functions for manufacturing are services.

If you are a manufacturing company that wants to be the best in your business for your customers, you’d better have excellent support services from core functions like product development and sales to more generic functions like human resources, IT, and accounting. If any of these support services function poorly, your customers are likely to be dissatisfied.

Lean Focuses on Flow

In my experience, people in services often think of lean as a manufacturing thing, and manufacturing is seen as a very different animal. But, are they really so different? It is true that a physical manual assembly job or a machine operator is easier to visualize than a job involving thinking or interacting with customers. Lean focuses on flow. For instance, you can physically arrange equipment or assemblers into some kind of flow. Lean works to stabilize processes, and it is easy to visualize how to make equipment more stable through preventative maintenance or make a person more stable through standard work.

But, how does this apply to a bunch of people sitting in an office?

The answer is that every type of work is based on an underlying process which can be visualized. Sometimes we can physically see it, and sometimes it must be drawn in some way to visualize it. Processes that are repetitive are easier to visualize. This is true in both manufacturing and services. The biggest complaint we hear among many manufacturers considering lean is that they engineer to order or make a large variety of parts that go through different sequences of processing so they cannot standardize the process. In services, we see many processes, such as filling out a standard invoice, that are far simpler than in manufacturing. Therefore, the real challenge is not improving manufacturing versus service, but improving routine versus non-routine work.

It is clearly more difficult to improve the flow of non-routine work. Think about a doctor performing surgery. Every patient is different, and the circumstances can change second by second during the operation. Yet, even in this case, we can begin by improving all of the systems that support the surgeon— the right tools and materials available at the right place at the right time. The surgery itself is more difficult to standardize, yet there is a movement toward “evidence-based practices” that seeks to provide standard approaches to common types of treatment. These should act more as guidelines, rather than standard work to follow precisely, but it is a way to accumulate knowledge to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of healthcare.

Custom software development is another type of service process that, on the face of it, seems complex and impossible to structure as a standard process. Yet, it is now being done everyday. Take, for example, Menlo Innovations that develops only custom software. Every customer’s problem is unique, and Menlo spends an exceptional amount of time observing the customer, using a role called the “high-tech anthropologist.” Then, day by day, the software is designed to be easy to use and effective for that particular customer. Even the software language used can change from project to project. Yet, at a high level, Menlo uses the same process for every project.

Meeting Customer Needs at Menlo Innovations

It starts with a standard way of understanding the customer and turning that understanding into brainstormed ideas followed by sketches of computer screens, which ultimately get broken down to individual features described one by one on note cards. A team of people guestimate the time it will take to program each feature. Customers are shown the array of features, and the cost of each card based on the estimates. Day by day, programmers select the next card and program it, test it, and validate it through a quality advocate. Then, each week the customer tests it and decides what cards to “play” the next week. Learning is continuous. Knowing what to work on when and getting rapid feedback helps to advance the process quickly and provides programmers with a framework for innovating and feeling a sense of accomplishment. In fact, the book Joy, Inc. about Menlo argues that the structure provided is a necessary condition for a joyful experience for both programmers and users of the software.

The Bottom Line

As a general rule, when approaching process improvement, we recommend starting simple. We would not start learning the piano by trying to play a Mozart concerto, and we should not start learning how to improve processes by working on the most complex, variable processes. If there are many products in the factory, start with relatively high volume, similar families of products before tackling the unique products rarely ordered. If there is a complex thinking process in a service, start with the more routine processes that support the thinking process. How can we remove as much of the variability as possible so that people can innovate within a stable structure?

The main point is that we sometimes have to observe and think deeply to find the underlying process. We may have to experiment with various ways to represent it visually. But, be sure there is, or at least can be, a repeating process at some level of abstraction. Find it, improve it, and you are on the road to freedom to innovate for higher customer value.

Dr. Jeffrey Liker is professor of industrial and operations engineering at the University of Michigan and author of The Toyota Way. He leads Liker Lean Advisors, LLC and his latest book (with Gary Convis) is The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership.

Karyn Ross contributed to this article.

- Category:

- Industry

- Manufacturing

Some opinions expressed in this article may be those of a contributing author and not necessarily Gray.

Related News & Insights

Manufacturing

Value Stream Mapping - Getting Quantitative Value from the Method

Opinion

May 06, 2014Advanced Technology, Automation & Controls

Four Use Cases for AI's Growing Role in Manufacturing

Industry

November 25, 2024Data Centers

Gray Expands Reach with Dallas Office

Corporate News

November 14, 2024