Defining the Opioid Crisis: Understanding the Problem Shapes Manufacturers' Response

The national health emergency of drug addiction, especially the opioid crisis, is reshaping the American manufacturing workplace. Amid shocking statistics and persistent problems, pioneering workplace leaders, support organizations and state and local policymakers are offering plans for action that raise hopes of turning the tide.

Defining Terms

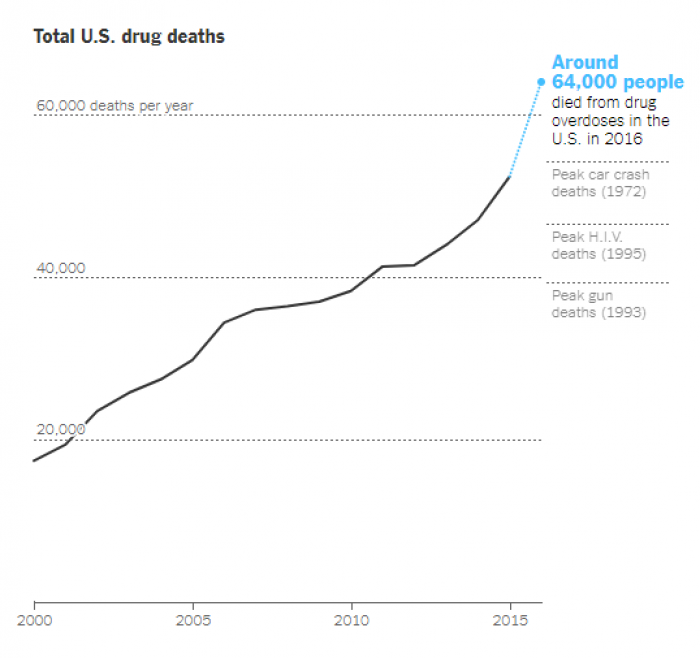

According to the New York Times, drug overdose deaths in 2016 in the United States exceeded 59,000 and showed the largest annual increase ever recorded. Drug overdose is now the leading cause of death for men under 50, and opioids account for 80 percent of overdose deaths. While the numbers are staggering, Dr. Andrew Kolodny, who recently joined Brandeis University’s Heller School as co-director of the Opioid Policy Research Collaborative, believes that viewing the problem of addiction through the narrow lens of overdose deaths misses the point — and limits ideas about potential solutions.

“While it’s true that some people developed an addiction from recreational use, many also became addicted taking opioids exactly as prescribed by doctors,” Kolodny stated. “Once addicted, they need to keep using opioids to avoid feeling awful.”

Becoming Proactive

Manufacturing workplaces face unique concerns especially when two million manufacturing jobs are expected to go unfilled over the next decade. Opioid use and declining labor force participation for prime-age men and women are inextricably linked. Recent Princeton University research says survey evidence indicates that almost half of prime-age non-labor-force (NLF) men take pain medication on a daily basis, and that as a group, prime-age men who are out of the labor force spend over half of their time feeling some pain. A follow-up survey finds that 40 percent of NLF prime-age men report that pain prevents them from working on a full-time job for which they are qualified, and that nearly two thirds of the men who take pain medication report taking prescription medication. Since 2007, women’s labor force participation has edged down almost in parallel with men’s.

Research by business insurer CNA indicates that among manufacturing industry workers, 6.5 percent engaged in illegal drug use. What remains to be seen is the extent to which prescription painkillers play a role in the manufacturing industry.

In this environment, a clearly established drug- and alcohol-free workplace policy is only the beginning. Effective employee intervention programs for manufacturers also include:

- Helping employees work with their doctors: Employees should know to discuss their concerns about taking an opioid painkiller as soon as a healthcare provider recommends it and determine whether a non-opioid can be prescribed instead.

- Better supervisor training: Managers need education about the difference between dependency and addiction and how to intervene before employees develop serious addiction.

- Support for confidential access to treatment: Emphasis on firm workplace policies needs to be balanced with promotion of employee-assistance programs.

- Drug testing: According to the National Safety Council, drug-free workplace policies supported by drug tests were more easily enforced when illegal drugs were the only drugs banned. Because legally prescribed opioids can affect shop floor performance and endanger employees, manufacturing companies need an array of drug-testing policies. Alliances with health insurers, workers’ compensation plan providers, educational institutions and training organizations can improve testing as well as access to treatment.

Slowdown Ahead?

While researchers and policymakers are pushing for solutions to the opioid addiction crisis, there isn’t yet a good understanding of what will work. Lawmakers are trying to find effective strategies while avoiding ideas that might have negative unintended consequences. Meanwhile, researchers such as those at Heller School’s Opioid Policy Research Collaborative are working to provide policymakers with much better information.

“The problem is they’re dealing with an emergency, and in an emergency, you’re often shooting in the dark,” Kolodny pointed out. Better information means everyone involved can aim more carefully.

“You definitely have policymakers at the state and local level who realize, due in some part to the work of Heller, that the opioid issue was fueled by aggressive prescribing,” Kolodny stated.

Recent reports show there might be slowdowns ahead in the opioid supply chain. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration is taking steps to reduce the manufacturing of controlled substances by 20 percent in 2018 compared to 2017.

Under the proposed notice published in the Federal Register, the targeted Schedule II painkillers to be reduced include oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, codeine, meperidine and fentanyl.

The annual Quest Diagnostics Drug Testing Index reveals some hopeful signs. Prescription opiate positivity – including hydrocodone, hydromorphone and oxycodones – declined in testing among the general U.S. workforce. Oxycodones have exhibited four consecutive years of declines, dropping 28 percent from 0.96 percent in 2012 to 0.69 percent in 2016. Hydrocodone and hydromorphone both showed fractional declines in both 2015 and 2016; 0.92% in 2015 to 0.81% in 2016 and 0.67% in 2015 to 0.59% in 2016, respectively.

And after four straight years of increases, positive testing for heroin held steady in the general U.S. workforce last year and declined slightly among federally-mandated, safety-sensitive workers.

Increased awareness, combined with improved workplace policies and partnerships with support organizations, is showing the way for manufacturing companies to attack the opioid crisis.

- Category:

- GrayWay

Some opinions expressed in this article may be those of a contributing author and not necessarily Gray.