Why Enriching People is More Important Than Rewarding Them

The simplest and most efficient assumption about what drives people is that we are all like computers maximizing our expected utility. We crunch numbers in our head and figure out the costs and benefits of alternative actions and select the path with the highest payout. That was the original assumption of Frederick Taylor and Scientific Management and, along with more efficient work methods that the experts designed, he was able to motivate people to dramatically improve productivity.

So, what’s in it for me?

The idea that you get what you measure and reward is deeply rooted in the psyche of most management throughout the world. It is particularly rooted in Western countries that have highly individualistic cultures where the individual wants to know: “What is in it for me?” Yet, Toyota goes out of their way to try to weed out hiring people who ask: “What is in it for me?” They violate a fundamental tenet of management thought.

Quality guru Dr. Demings said: “People with targets and jobs dependent upon meeting them will probably meet the targets—even if they have to destroy the enterprise to do it.” Deming preached against numerical targets, annual performance appraisals and pay by the piece. What is wrong with incentive pay and how can management possibly motivate people if it is not through contingent pay?

Examining contingent pay through behavior modification

We learn a lot about contingent pay through the field of psychology known as behavior modification. One of the formative events in this field is the famous Pavlov’s dog. Pavlov was studying the physiological digestive process, but noticed a curious phenomenon. He noticed that the dogs in the experiment began to salivate in the presence of the technician who normally fed them, rather than simply salivating in the presence of food. He explained this as a “conditioned response.” The dogs were fed by the technicians and their brains came to associate the technician with the food. He observed “anticipatory salivation” even when there was no food present. This same principal makes life easy for managers. Identify a reward that matters to the worker, make it contingent on desired behaviors, and use the correct reinforcement pattern. People, like dogs, will do what you want without even realizing they are being manipulated. They do not even have to be rewarded 100 percent of the time once you establish a conditioned response.

Why reinforcement patterns don’t work

There are some problems with this. One of the most powerful barriers to high performance work systems is precisely this type of system of reinforcement. I have seen a number of cases of companies that had established piece-rate systems. But, with high performance systems we are not interested only in producing many pieces. We are interested in the right pieces, the right quantity, the right timing, and the right quality. Overproduction is the fundamental waste. Try telling that to someone paid by the piece. “When this buffer is filled, please stop producing and we will reduce your pay.” Good luck with that. And much of today’s work is more complex than the iron ore shoveling that Frederick Taylor was improving.

In the modern age we have much more complex work, even in manufacturing, and we want people to think creatively and adapt to different situations. Continuous improvement suggests that workers are involved in the process of creatively thinking about how to do their jobs better and are enthusiastic about it. There is actually evidence that contingent, extrinsic rewards can reduce both our creativity and our enthusiasm about engagement in our work.

How extrinsic rewards actually reduce creativity

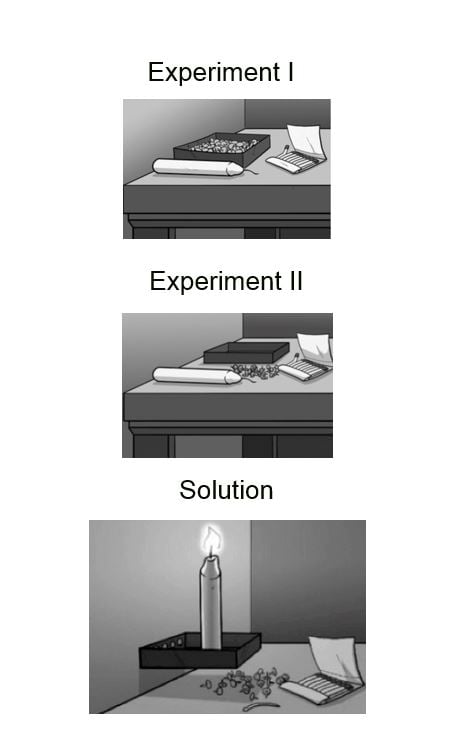

One of the most famous experiments to demonstrate the limits of extrinsic rewards is the candle problem, first developed by Samuel Gluckberg in 1962. The task was to attach the candle to the wall and light it, without the wax dripping on the table. Subjects were given the candle, a box of thumb tacks, and a box of matches. In experiment I (tacks in box), a set of subjects was offered money if they were the fastest to accomplish the task. The other set were not offered a monetary reward but asked to help in setting a baseline for the research. The group offered money consistently lost the competition—they took longer. In experiment II (tacks out of box) Samuel then changed the experiment in only one way. He took the tacks out of the box and put the alongside the box. Now those offered the monetary incentive performed better. Why would that be?

He explained that financial incentives focus our behavior on doing tasks in the single best way we know how. In experiment 1, the incentivized group quickly tried to get the candle on the wall using the tacks or melting the wax on the candle and what they tried did not work. The non-incentivized group was more reflective and more quickly figured out that if they took the tacks out of the box they could attach the box to the wall with the tacks and set the candle in it. In experiment II, since the tacks were already out of the box it was more obvious that you could use the box to hang the candle, the incentivized group raced and did this faster and won.

The implication: if we want creativity then we must go beyond simple “if-then” financial rewards. In fact, these types of rewards will reduce creativity. Increasingly, work is becoming complex, and even with simple, repetitive work we are looking for employees to think creatively about how to improve their work. Quantity is not enough. We want high quality. This means we will need to come up with more creative ways to reward people. Make work enriching so people get satisfaction by doing the work. Reward people more holistically for the success of the business through gain sharing and profit sharing or even through shares in the business. For twenty-first century work and expectations, we will need more creative ways to motivate people.

Dr. Jeffrey Liker is professor of industrial and operations engineering at the University of Michigan and author of The Toyota Way. He leads Liker Lean Advisors, LLC and his latest book (with Gary Convis) is The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership.

- Category:

- Industry

Some opinions expressed in this article may be those of a contributing author and not necessarily Gray.